Resistance to the Soviet regime in estonia 1940-1991

On 20 August 2021, 30 years passed since Estonia’s independence was restored. Before this, for more than half a century, Estonia was occupied – by the Soviet Union for most of that time, but also by the Germans for three years during World War II.

Like Latvia and Lithuania, Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940. The incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet sphere of influence was agreed upon by Vyacheslav Molotov, the people’s commissar for foreign affairs of the USSR, and Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. On 23 August 1939 they signed a non-aggression pact between their two countries, which included a secret protocol dividing Eastern Europe into their respective spheres of influence. This day was commemorated 50 years later, on 23 August 1989, when the Baltic nations attracted international attention with the Baltic Way – almost 2 million people stood in peaceful protest in a 400 mile long human chain, stretching from Tallinn, Estonia to Vilnius, Lithuania and focused attention on the injustice of the half-century-long Soviet occupation and the tens of thousands of victims. The date of 23 August is now commemorated as a day of remembrance in Europe.

Resistance to the occupation in Estonia began immediately in 1940. For instance, opposition candidates were nominated for the staged puppet parliamentary elections in July 1940. This was bloodless civil disobedience, but in the summer of 1941, when the Second World War reached Estonia, armed resistance began. Especially after the deportations of June 14, 1941, men and women sought refuge from Soviet persecution and terror by fleeing to the forests. They organised themselves into local units, and despite a shortage of weapons, the partisans, known as Forest Brothers, were able to seize power in many parts of southern Estonia and raise Estonian flags before the German troops arrived.

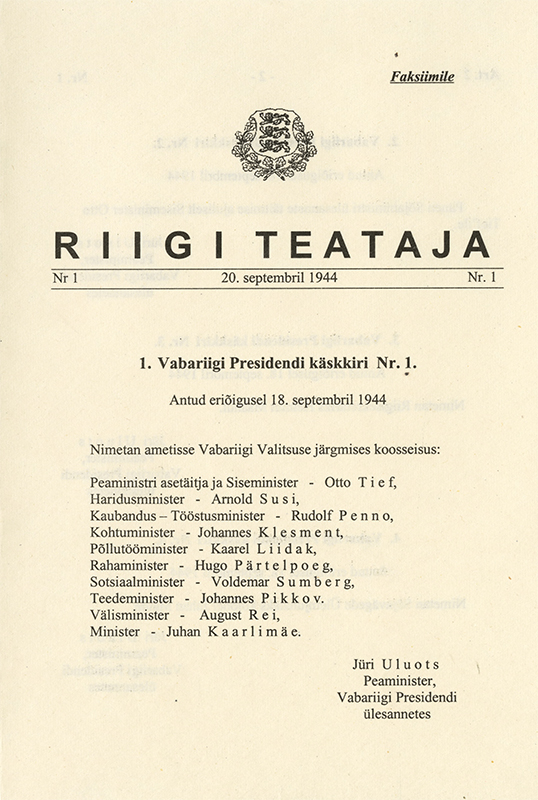

In the summer of 1941, the German occupation authorities refused the Estonians’ request to restore their independence. They also refused to recognise it when Jüri Uluots, the last Prime Minister, acting in the role of the President of Estonia, instructed his deputy, Otto Tief, to form an Estonian government in September 1944. An Estonian government was formed, but only in exile in Sweden. Most Western countries refused to officially recognise the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states. Thus, in many countries, the diplomatic missions of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia continued to operate.

In the autumn of 1944, after the return of the Red Army and the Soviet authorities, armed resistance by the Forest Brothers continued – in some places, it persisted until the early 1950s. Soviet security forces arrested thousands of people. The mass persecution and terror culminated in the deportation of more than 20 000 people in 1949. Most of these were women, children and the elderly. The strength of the Forest Brothers started to falter due to despair – they had neither hope of foreign assistance nor equipment, and the deportations and the elimination of private farms had destroyed their last remaining strongholds. This was crucial in the Estonian climate, since one needs a safe household to hide in. The Forest Brothers acted in small groups, having no or very little contact with other units. It was a spontaneous resistance in the name of national freedom. More than half of them were arrested by the Soviet security forces and 10% were killed for protecting their country.

However, resistance did not end. In many places, school students formed secret societies. These defied the Soviet regime with pro-Estonian activities, the hoisting of the banned national flag and other actions that demonstrated their rejection of the occupation forces and their desire for the restoration of Estonian independence. Many of them were sentenced for 10–15 years of imprisonment in Soviet prison camps.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the dissident movement gained momentum. However, unlike dissidents in Russia, who opposed the regime for what it was, dissidents in the Baltic states aimed to draw attention to the illegality of the occupation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and to demand the restoration of independence. They publicly criticized the Communist regime and reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications (samizdat), often by hand, passing the documents from reader to reader, thereby also communicating information about Communist crimes to the free world as much as possible. The practice of manual reproduction was widespread because typewriters and printing devices required official registration and permission to access them. As ridiculous as it may sound for this activity, dissidents were often sentenced for around 5 years of imprisonment in prison camps or forced into mental hospitals, another method of repressing people in Soviet Union.

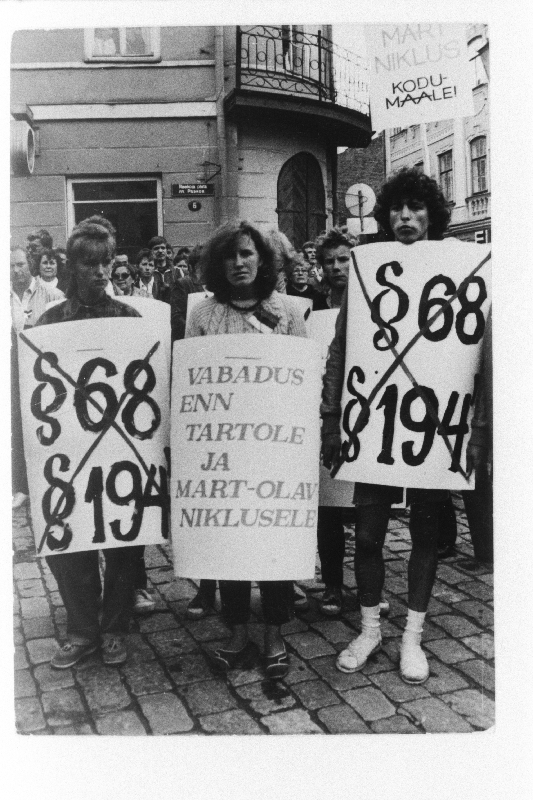

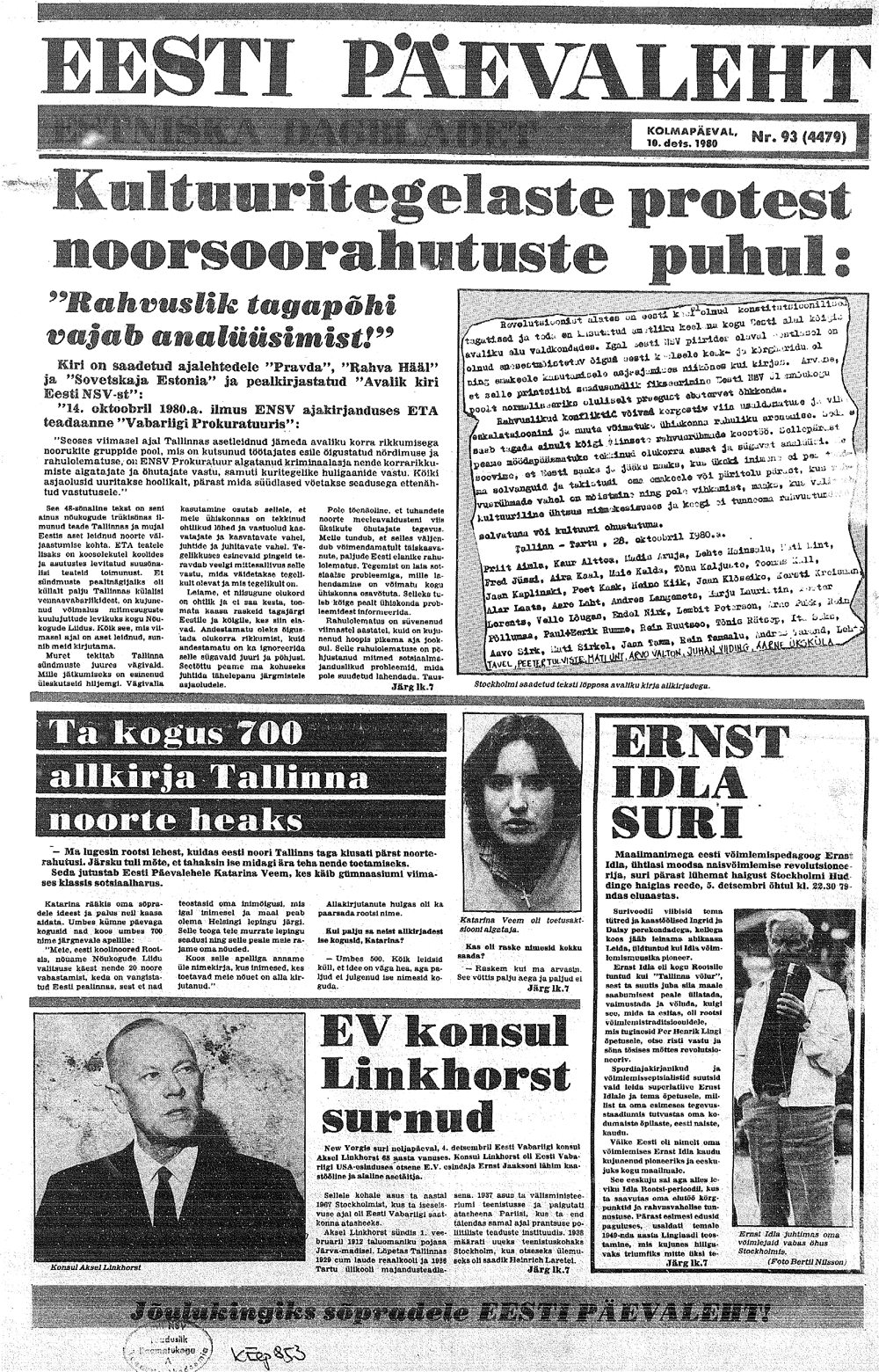

In the late 1970s, Soviet society increasingly started to show signs of decline. For Estonians, the seemingly unchecked influx of non-Estonian-speaking people from other parts of the USSR was an increasingly serious problem. The same was true of Russification – the pressure to switch to Russian-speaking administration in many areas of life. The semi-spontaneous riots by Tallinn schoolchildren in the autumn of 1980, which were brutally suppressed by law enforcement agencies, prompted forty intellectuals to write an open letter in protest. Known as the “Letter of the 40,” it was sent to major newspapers in Estonia and Moscow. Those publications, of course, did not publish it. However, this text made its way abroad and was also secretly disseminated in Estonia. The signatories to the letter were not imprisoned, but many were no longer permitted to continue working in their fields. As a consequence, the Soviet Union became well known for having manual workers with an extremely high education.

Refugee communities played an important role in keeping international attention focused on the freedom struggle of the Baltic nations. During the Second World War, tens of thousands of people had fled the Baltic states to the West – initially in the hope that they would be able to return soon thereafter. They informed the governments and residents of their host countries and international organisations about the situation in their occupied homelands and called for the non-recognition of the occupation to continue. They raised their children to be Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians and maintained their national cultures, education, intellectual pursuits and economics in their mother tongues. After regaining independence, they supported their homelands’ return to the Western world and a final separation from the post-Soviet sphere.

In 1991, this struggle was successful. Estonians restored their independence. But that was not the end of the story: all Estonians must continue to work every day to maintain this independence and freedom.

The Summer War

In the summer of 1940, the Soviet Union occupied the Republic of Estonia. In 1941, roughly 10 000 men, women, and children were deported against their will from Estonia to Siberia in the USSR. Most of the men were sent to Gulag prison camps while the women and children were subjected to forced resettlement. The war between the USSR and Germany, which began on 22 June 1941, led to a spontaneous revolt against the Soviet authorities. Amid the ongoing Soviet terror, Germany, that had hitherto been the historic enemy, now was seen as a liberator. People hid in the forests and formed armed partisan groups, known as Forest Brothers; their attacks on the rear of the Red Army undermined morale. Bridges and communication lines were destroyed. Smaller Soviet units, primarily representatives of Soviet rule and Soviet institutions, were attacked and, in many municipalities, taken over before German troops arrived. Estonian guides, spies, and interpreters provided support for German army units. Thousands of men fought as Forest Brothers, as well as in Estonian companies and battalions that were formed under German divisions. For Germany, the war was a German war on the Eastern Front; thus, local volunteers were not recognised as allies in 1941 and were disbanded after the German takeover. Units of the Forest Brothers were formed into the Omakaitse (Home Guard), a sort of auxiliary police. Its task was to maintain order in Estonia, both in the German rear, as well as after Estonia was taken over by the civilian occupation government.

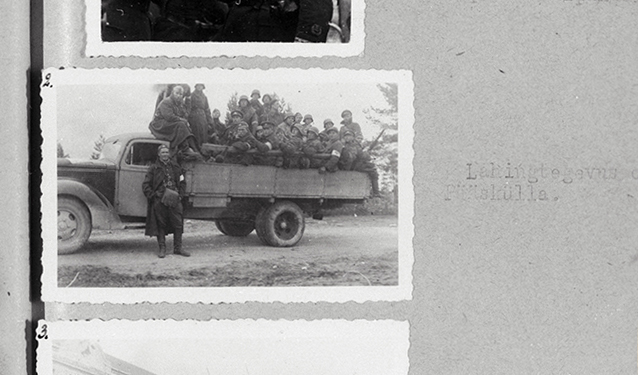

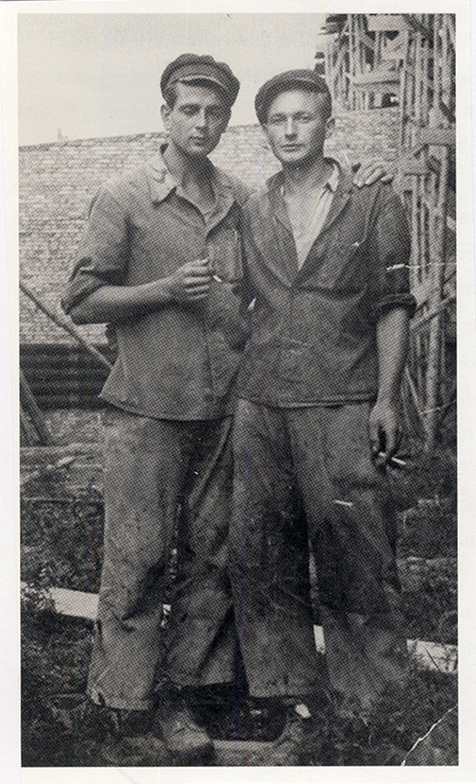

Forest Brothers from southern Pärnu County who arrived in Pärnu on 8 July 1941 with the German advance guard. Some Forest Brothers are in the uniform of the Defence League, liquidated after the occupation of Estonia in the summer of 1940, while others wear an armband of the Defence League as insignia.

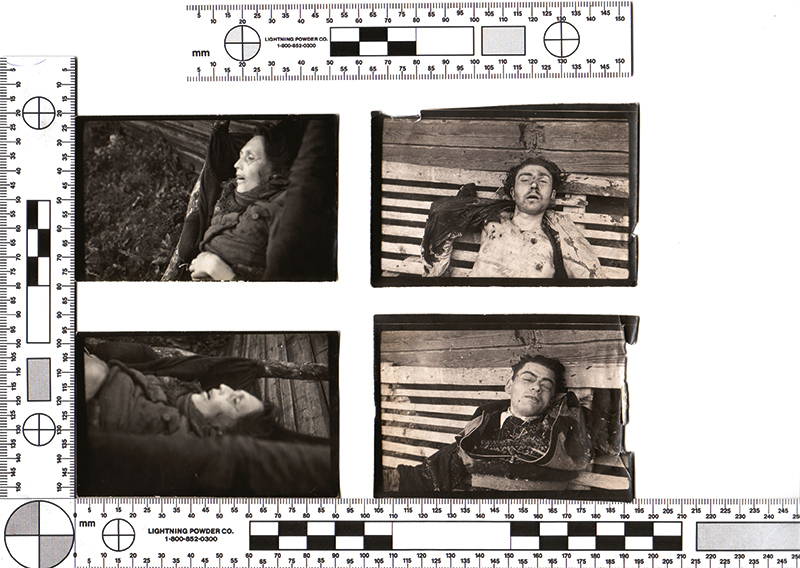

Ruins of a farm in Kautla. As a revenge for helping Forest Brothers, a married couple living in the farm was killed, with the farm burned down by an extermination battalion of the interior ministry of the Soviet Union on 31 July 1941. In July and August 1941, one of the largest groups of Estonian Forest Brothers operated in the Kautla area; it was formed by the Estonian intelligence group ERNA, sent from Finland. ERNA, a long-range reconnaissance group, was a Finnish Army unit of Estonian volunteers that fulfilled reconnaissance duties in Estonia behind Red Army lines during World War II. The unit was formed by Finnish military intelligence with the assistance of German military intelligence for reconnaissance operations.

Interesting facts

In the summer of 1941, hundreds of soldiers and officers of the 22nd Estonian Territorial Corps of the Red Army and border guards on the Estonian-Latvian border deserted their units and joined the Forest Brothers. Right after occupying the country the 22nd Territorial Corps was formed from soldiers and officers of the Estonian army, which had been disbanded in 1940. The 22nd Territorial Corps was consequently put under the authority of Red Army officers and political leaders. Estonian border guards had been left to guard the border with Latvia even after the incorporation of Estonia and Latvia into the USSR.

On 10 August 1941, the last Prime Minister of the Republic of Estonia, Jüri Uluots, informed the German occupation authorities on behalf of the Republic of Estonia that Estonia was willing to participate as an ally in the fight against Bolshevism. The Germans did not respond to the proposal.

In the summer of 1941, the Forest Brothers units had up to 12 000 fighters, of whom approximately 4 000 took part in combat. About 800 Forest Brothers had fallen or gone missing in the Summer War in 1941.

Legal continuity, non-recognition policy

The Republic of Estonia was restored in 1991 on the principle of legal continuity. Estonia is the same republic that was established on 24 February 1918 and was occupied by the USSR in the summer of 1940. As early as 23 July 1940, US undersecretary of state Sumner Welles declared that the United States did not recognise the occupation and annexation of the Baltic states. After World War II, most Western democracies joined the policy of non-recognition of Soviet occupation.

In autumn 1991, Western countries recognised the restoration of Estonia’s independence and restored diplomatic relations with Estonia. From 1940 to 1991, Estonian foreign missions in the United States, the United Kingdom, and some other countries maintained Estonia’s legal continuity. The Estonian government-in-exile operated with the Prime Minister in the role of the President of the Republic. In October 1992, the last Prime Minister, Heinrich Mark, acting as President of the Republic, handed over his authority to Lennart Meri, who was the elected President on the basis of the new constitution adopted in the summer of 1992.

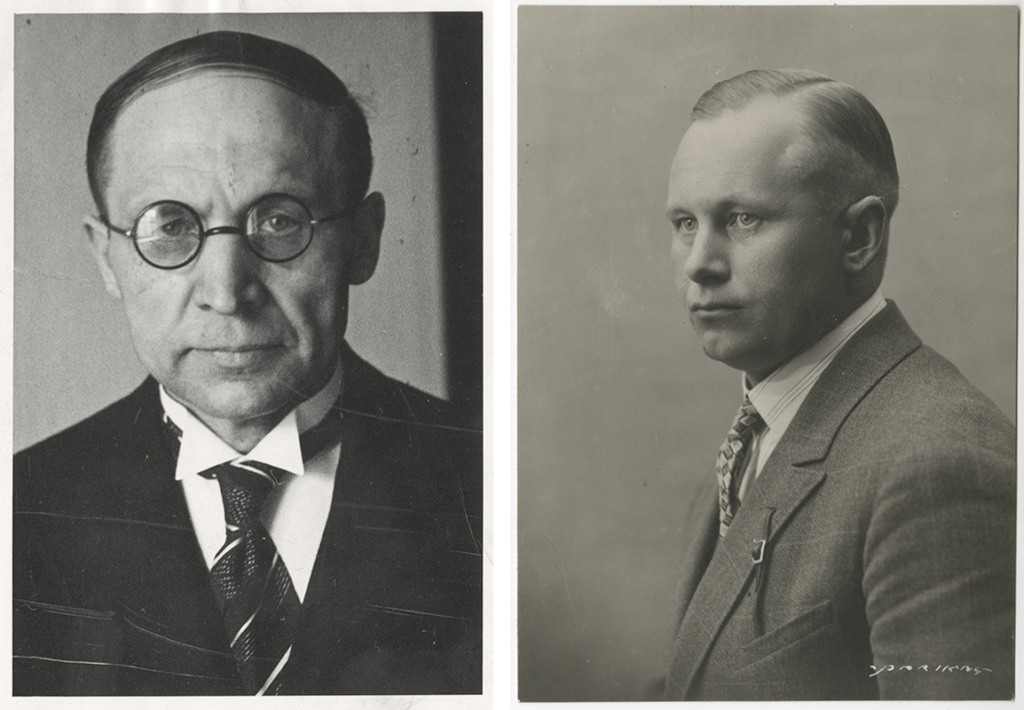

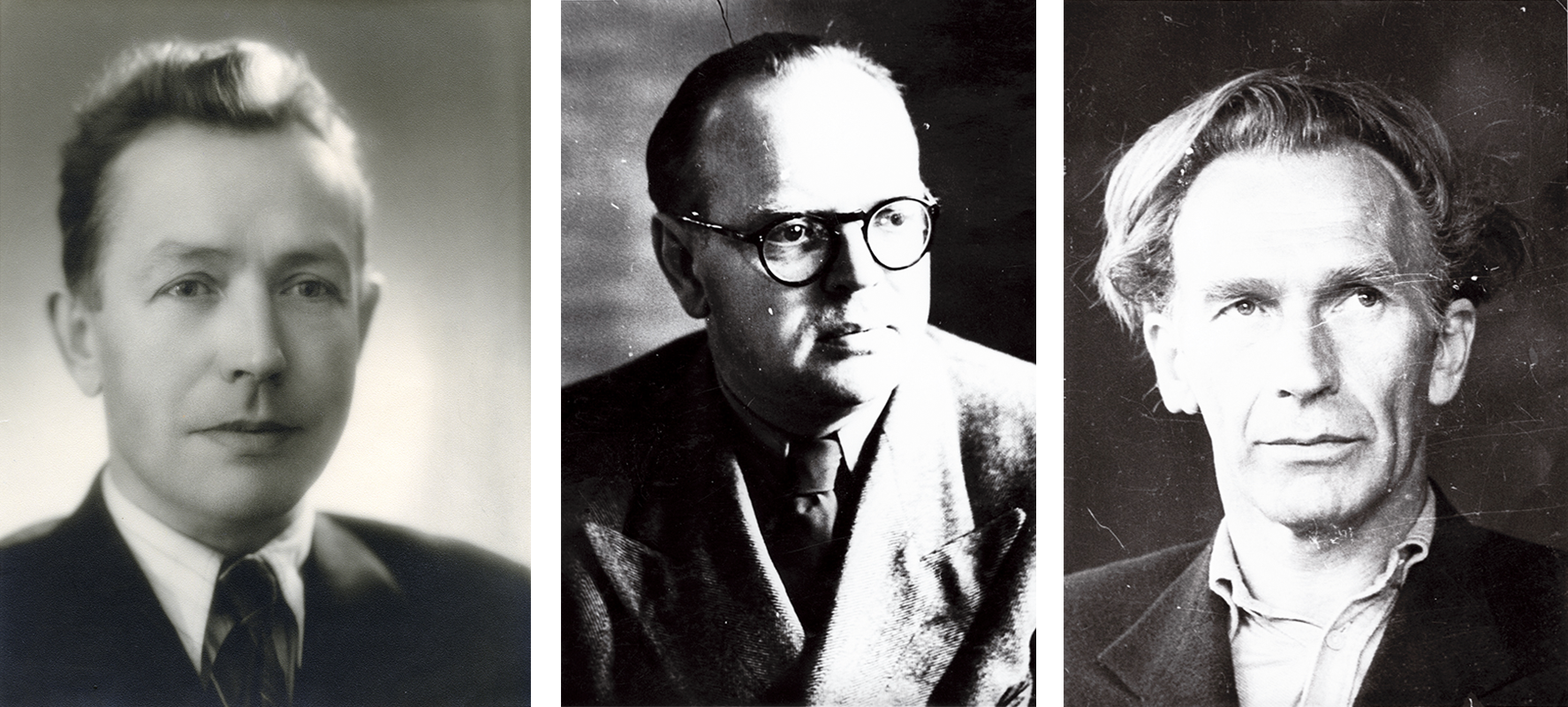

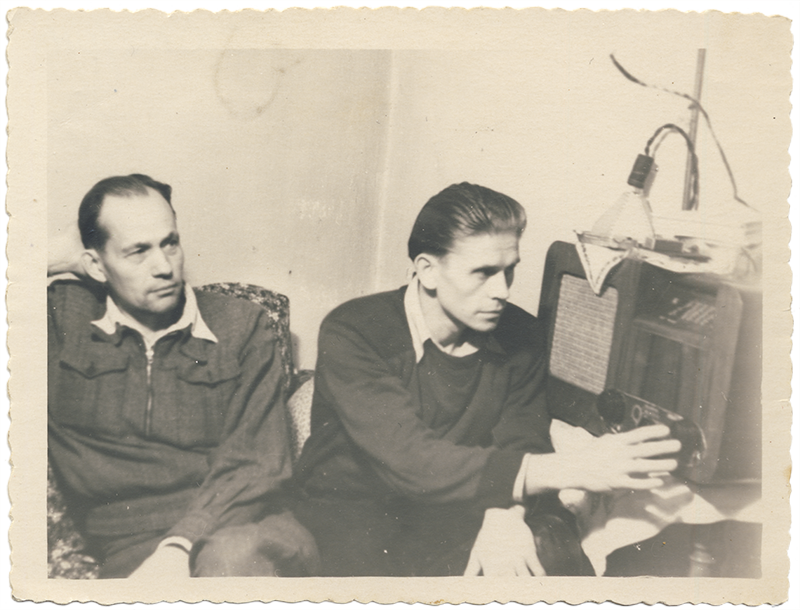

Jüri Uluots (left), Prime Minister in the role of the President of Estonia.

and Otto Tief (right), the acting prime minister of the last government of Estonia.

On the evening of 18 September 1944, Jüri Uluots instructed Otto Tief to form a government: “The Germans are withdrawing from Estonia. It’s time to act! Gather the members of the government and take action”.

Interesting facts

To protest the Soviet army’s invasion of Afghanistan, 28 countries boycotted the 1980 Moscow Olympics, and another 16 countries competed under the Olympic flag instead of their national flag.

Tallinn was the venue of the sailing regatta for the Moscow Olympics. The Olympic Games, with its ideals of peace and friendship, was therefore held on occupied territory. This meant that countries that sent athletes to Estonia implicitly recognised Soviet rule over Estonia. Therefore, some countries boycotted the Tallinn regatta. A few other countries, such as Spain, competed in Moscow under their national flag but in Tallinn only under the Olympic flag.

The Forest Brothers

Forest Brothers were people who confronted the occupation with armed underground resistance. Men and women hid themselves in bunkers that were built in forests and bogland, lived on farms that were located in sparsely populated areas, and attacked Soviet officials and security officers, as well as active members of the party and soviets (councils). After World War II, thousands more people hid from the Soviet authorities for fear of persecution but did not participate in armed resistance. Altogether, there were up to 15 000 Forest Brothers and people in hiding at various times.

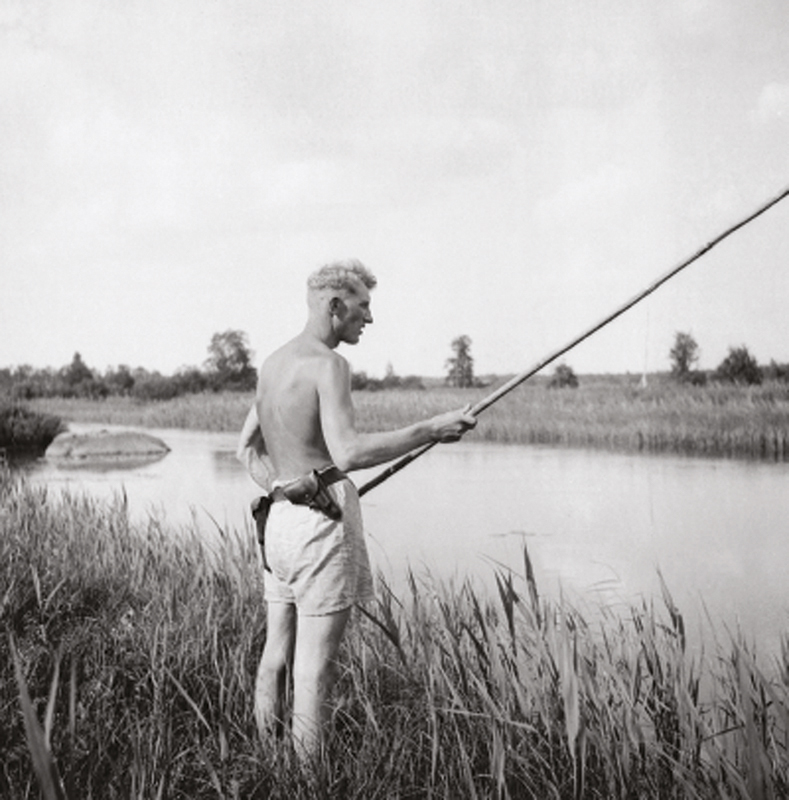

The largest organisation of Forest Brothers was the Relvastatud Võitluse Liit (Armed Combat Union, 1946–1949). Armed clashes between the Forest Brothers and Soviet security forces occurred frequently until the mid-1950s. Minor clashes occurred later as well. Many people remained in hiding for decades. The last Forest Brother was August Sabbe, who was killed during his arrest in 1978 when caught fishing close to his birth home.

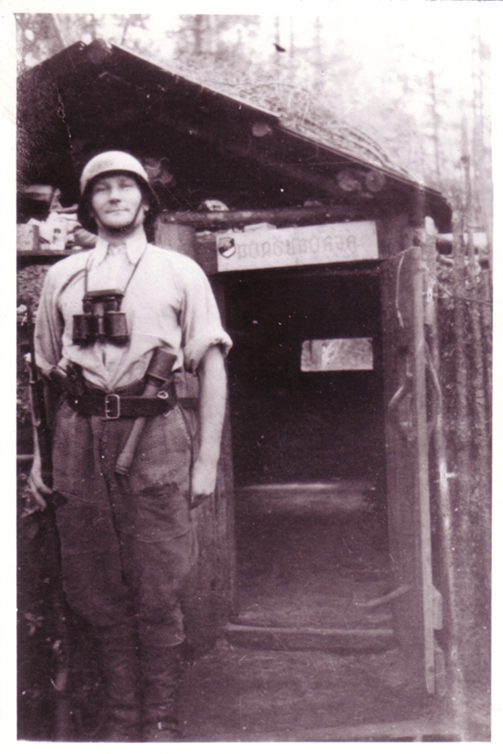

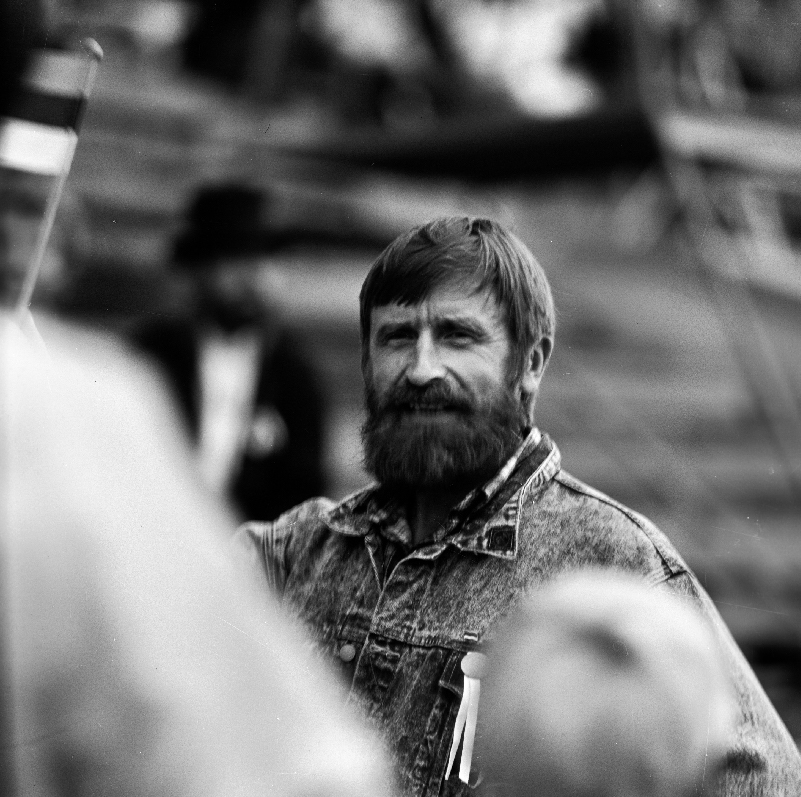

Forest Brother Jaan Roos in front of the door to Põrgupõhja bunker. Põrgupõhja bunker was the headquarters of the nationwide resistance organisation known as the Armed Combat Union until it was destroyed in a raid on 31 December 1947. Soviet security soldiers shot Jaan Roos dead in front of the door to the bunker.

The Forest Brothers required food and ammunition. To obtain these, they needed more than just support from farmers. Soviet shops, public offices, and similar targets were also robbed. The group of the legendary Võrumaa Forest Brother Jaan Roots counts money after a robbery. Jaan Roots was killed in a raid on 6 June in 1952, along with nearly all his comrades.

Interesting facts

The arrested Forest Brothers were usually sentenced to 10 or 25 years in a Gulag prison camp. After Stalin’s death in 1953 and the general reduction of sentences, some Forest Brothers were released and returned home. However, not everyone was allowed home. Harald Kiviloo (b. 1928), arrested in 1957, served all 25 years of his prison sentence. After his release in 1982, he was not allowed to live in Estonia and moved to Latvia.

In hiding for 41 years, Paul Rets (b. 1904) died in 1987 in Lebavere village on the farm of Minna Kiviking, who had been hiding him. In only four years, he would have seen Estonia’s independence restored.

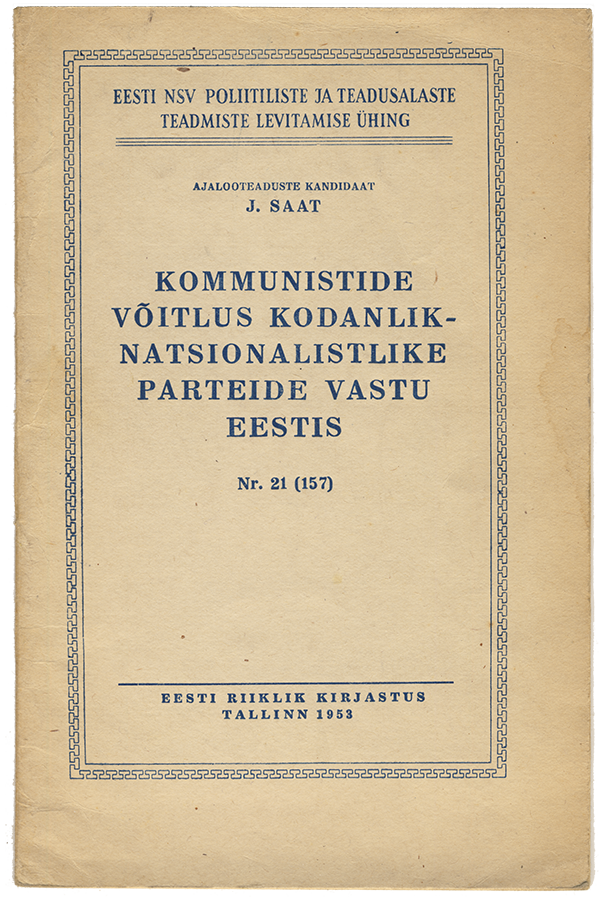

“Bourgeois nationalism”

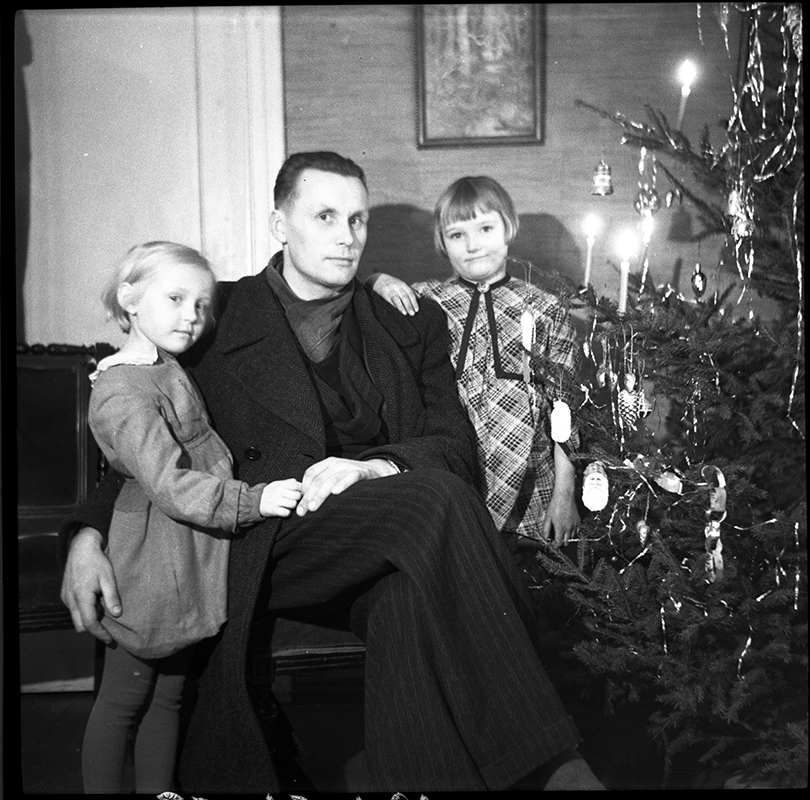

After Estonia was reconquered in 1944, the process of Sovietisation that had begun in 1940 continued for many years and was met with active and passive opposition. “Bourgeois nationalism” is an ideological Soviet term that identifies citizens by combining nationality and class. In addition, participation in public life in the era of independence or during the German occupation was regarded as “bourgeois nationalism” and was, in turn, closely associated with opposition to Sovietisation. Among those persecuted were farmers who refused to join the collective farms; churchgoers, who celebrated Christmas at home since religious beliefs were not welcomed by Communist ideology; people who did not participate in Soviet elections, in which only one candidate, approved by the Communist Party, stood for each mandate; or those who criticized Soviet values in the workplace or private conversations. Although Communist rhetoric continued to condemn “bourgeois nationalism” until the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was no longer an offense punishable by imprisonment in a prison camp after Stalin’s death. However, it still caused significant trouble for those accused.

Alfred Karindi (1901–1969), Riho Päts (1899–1977), and Tuudur Vettik (1898–1982) were Estonian composers and artistic directors of the 1947 Song Festival. All three were arrested on charges of “bourgeois nationalism” and “flirtation with the West”. Vettik and Päts were also reproached for writing and publishing “Song of the Forest Brothers” in 1941, during the German occupation. They were sent to a prison camp but released after Stalin’s death in 1953.

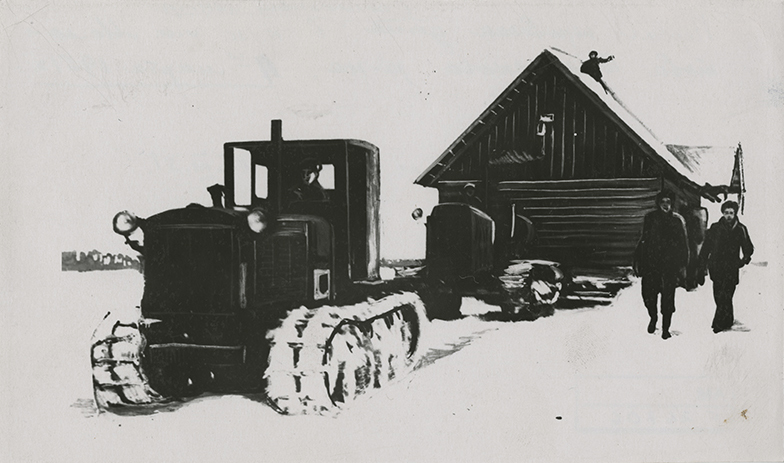

Relocation of a house to the collective farm centre at the Molotov Kolkhoz in Valga County, 1951. Estonian traditional villages are scattered. This was not acceptable for the Soviet occupation regime, as it reduced control over inhabitants and made it easier for them to help Forest Brothers. Houses were moved together with the residents, without asking for their permission, if the legal residents had already been deported to Siberia.

Interesting facts

In their slogans, Bolsheviks were supporters of all nations, but in practice, they obviously were Russian imperialists and very chauvinistic. It was quite usual that two Estonians speaking among themselves received from a bypassing Russian the rebuke “Govorite po chelovecheski!” (“Speak a human language!”), which contained the hint that Estonians are monkeys. The whole Estonian language could be interpreted by Bolsheviks as a tool for “bourgeoise nationalism,” a poison against which “proletarian internationalism” was the antidote. Internationalism could be promoted and developed only in Russian, obviously. For that purpose, Russian was named “the language of friendship between nations.”

Indrek Tarand (b. 1964), former member of the European Parliament, recalls his military service in Gatchina in Leningrad Oblast, Russia: “In 1983, twelve other Estonians and I entered the gates of battalion number 40304. The experienced conscript soldiers, mainly Russians, greeted us with the question ‘Where are you from?’ We replied in Russian that we were from Estonia. ‘Ah, the fascists have arrived!’ shouted the Russians. I dared to protest and explain that we were not fascists. One of them came to me and asked ‘What is ‘yes’ in your language?’ and of course I pronounced the Estonian ‘yes,’ which is ‘ja.’ The Russian guy grinned and said ‘You see, exactly the same as in German. So you are definitely fascists!’ No further proof or debate.”

Underground youth organisations

The Soviet authorities closed down all Estonian youth organisations; the only organisation permitted now was the Young Communist League and its “younger brother,” the Pioneers. However, young Estonians founded a number of underground organisations to preserve Estonian identity and carry out anti-Soviet activities. These organisations had names and statutes, and members swore an oath. They distributed anti-Soviet leaflets, tore down or defaced Soviet symbols, hoisted outlawed Estonian national flags in public places, collected and distributed banned literature, collected weapons, and assisted underground armed resistance (Forest Brothers). There were hundreds of secret youth groups, most of them undetected. The Estonian Association of Student Freedom Fighters has identified at least 82 anti-Soviet youth groups operating from 1945 to 1954 whose members faced prosecution; about 700 young people were arrested and sentenced to Gulag prison camps. The activities of underground youth organisations continued even after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Weapons and ammunition confiscated from Juhan Kuusk’s apartment. Juhan Kuusk belonged to an anti-Soviet youth group. Ageeda Paavel and Aili Jürgenson, who belonged to the same association, received explosives from him and blew up a Soviet memorial to the Red Army soldiers in Tõnismägi, Tallinn, on 8 May 1946. This was a counterattack to the occupying regime that had destroyed all the memorials of the Estonian War of Independence.

Ageeda Paavel was sentenced for 10 years in a Gulag prison camp, and Aili Jürgenson for 8 years. Juhan Kuusk (b. 1932) was arrested in 1946 and 1947, and escaped on both occasions. A search for him throughout the Soviet Union ended in 1973. According to some reports, he was shot during his second escape attempt in Arkhangelsk Oblast.

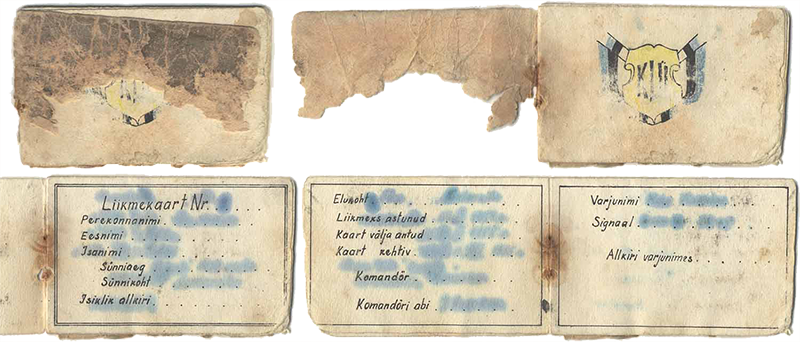

Vaba Sõltumatu Noortekolonn (Free Independent Youth Column) No. 1 pennant, 1988. The organisation was founded in 1987 in Võru. The young people tidied up the graves of those who fell in the Estonian War of Independence from 1918 to 1920 (something frowned upon by the authorities), protested the conscription of Estonian youth into the Soviet army, and so on. Ain Saar, one of the founders and leaders of the organisation, was forced out of the country by the KGB in 1988. Citizens of the USSR were not permitted to leave the “working peoples’ paradise” of their own free will. In most cases, people who had attracted attention in the West were forced to emigrate. This was the easiest solution for the KGB to get rid of them. Since the Helsinki Declaration in 1975, Soviet Union wanted to demonstrate that the regime respected human rights. Therefore, it was inconvenient for the authorities to imprison such people. For example, the Russian writer and dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was famous enough to be expelled, but the nuclear physicist, dissident and Nobel laureate Andrei Sakharov was sent to exile to Gorky (Nizhny Novgorod), a city that was off limits to foreigners. He lived there under the control of Soviet militia until 1986, when Mikhail Gorbachev released him.

Forcing someone to emigrate also meant revoking their citizenship, which was supposed to be humiliating but was actually rather relieving. At the same time, people sent to prison camps were to maintain their Soviet citizenship.

Interesting facts

The Eesti Rahvuslaste Liit (Union of Estonian Nationalists) differed from other youth organisations in that it was founded in the late 1950s by Estonian youth serving sentences in political prison camps in the Mordovian ASSR. Taivo Uibo, Enn Tarto, and Erik Udam, leading members of the union, were arrested again in 1962 and sent back to the prison camp. Enn Tarto was arrested a third time for anti-Soviet activities in 1983, and sent to a prison camp in Perm Oblast, from where he was freed in 1988.

Dissidence

Here, “dissidence” refers to unofficial movements in the USSR for human rights and civil rights. Dissidents publicly demanded that the USSR follow its own laws as well as international agreements, thus bringing the resistance to Communist rule out into the open. Dissidents were persecuted in many ways: they could be arrested, detained in special psychiatric hospitals, denied professional work (or any work), removed from the housing queue, and so on. (In the Soviet Union there was a queue for everything – housing, landline phone numbers, cars, even tyres, etc.)

One form of dissident activity was samizdat, the private printing and publishing of forbidden literature and anti-Soviet statements. Underground magazines were published, and public letters and appeals were compiled. Dissidents gathered evidence of human rights violations and crimes against humanity in the Soviet Union and distributed this information to the Free World. From there, such material appeared not only on radio programmes in Eastern European languages broadcast to those behind the Iron Curtain, but also in regular Western media. It was one of the channels for obtaining accurate information about life in the Soviet Union.

For spreading the truth about Communist crimes, dissidents often were sentenced for around five years to Gulag prison camps or forced into mental hospitals without actually having any mental problems, at least before serving time at the hospitals.

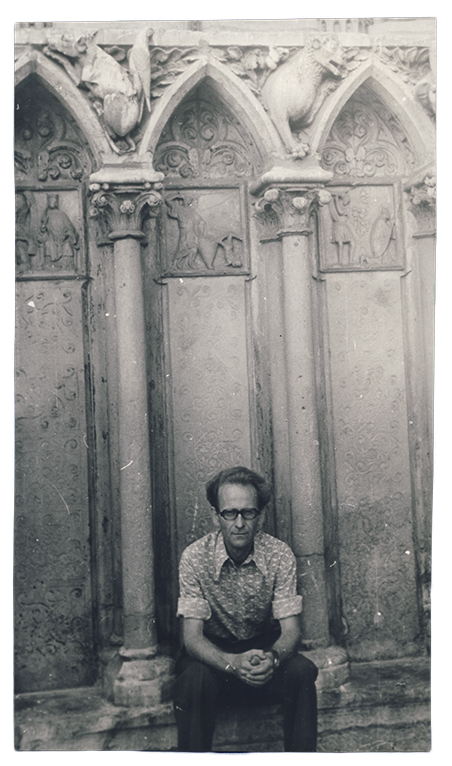

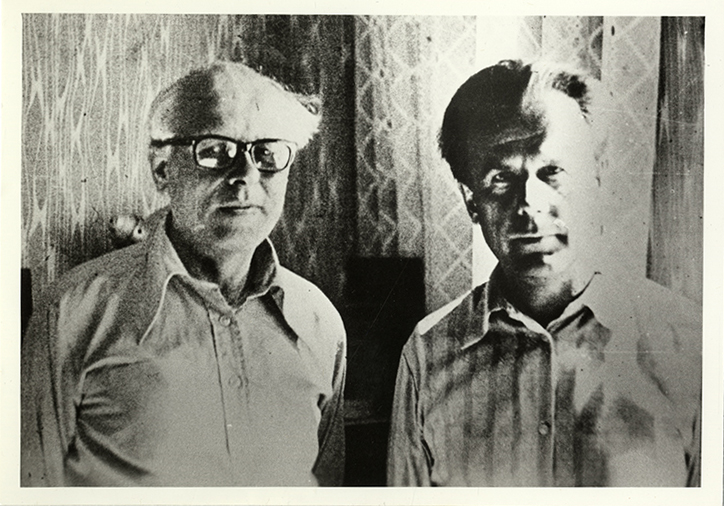

Mart Niklus (left) at the reburial of fellow fighter and fellow prisoner Jüri Kukk in Kursi Cemetery, 1989. Niklus and Kukk were both arrested in 1980 for anti-Soviet activities. Among other things, they demanded the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. Together they started a hunger strike in the prison camp; Jüri Kukk died in 1981 at the Vologda Prison hospital. Niklus was released in 1988. In 1958–1966, he had been imprisoned in a Mordovian ASSR prison for anti-Soviet activities.

Interesting facts

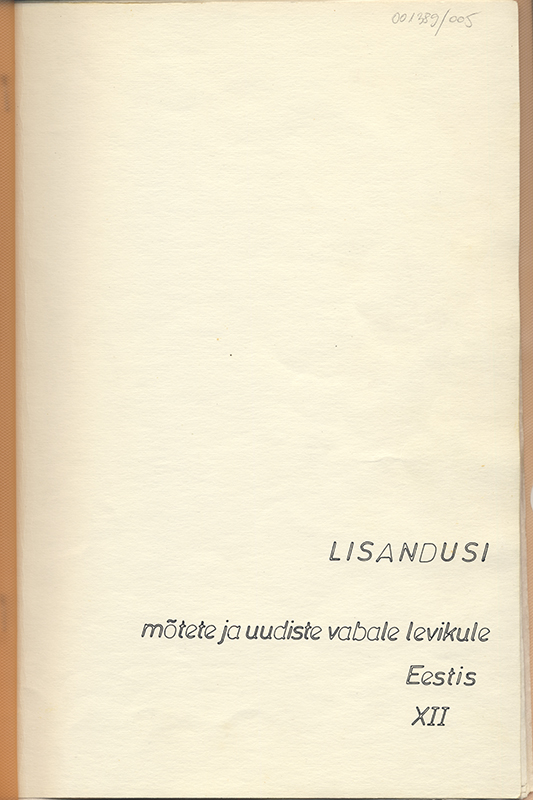

There was strict pre-censorship in the Soviet Union. All typewriters were registered, and a typographic sample was taken so that the particular typewriter used for typing any text could be identified. Mart Laar, appointed prime minister of the Republic of Estonia in 1992, had therefore smuggled his typewriter from Poland in the 1980s. It was used to print underground material, including Mart Laar’s first contribution to the underground magazine Additions. This typewriter is preserved at the Vabamu Museum in Tallinn, Estonia.

Public letters

One form of dissident resistance was the writing of public letters, of which the 1979 Baltic Appeal was the best known internationally. This was a joint statement by Baltic dissidents to UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, the governments of the Soviet Union and East and West Germany, and the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom. The appeal called for the annulment of the secret protocol of the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (that placed the Baltics in the Soviet sphere of influence), and the restoration of the independence of the Baltic states. The Baltic Appeal was signed by 45 dissidents; Estonian signatories included Mart Niklus, Enn Tarto, Erik Udam, and Endel Ratas. It was the first nonanonymous political request that people signed with their names. All of them were persecuted for it; indeed, everyone involved with the document or its distribution was punished. If not arrested, they lost their jobs. Previously known dissidents were imprisoned again. For example, Estonian Mart Niklus was sentenced to ten years in prison camp in which he had served for eight years.

Copies of the text were not only distributed in the Soviet Union but also smuggled to the West, even reaching US President Ronald Reagan. In response to the Baltic Appeal, the European Parliament passed a resolution in support of the Baltic states on 13 January 1983, the first such statement by an international organisation.

Dissidents were the ones who wrote to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and the government regarding human rights violations. Initiatives also came from circles not involved with the dissident movement.

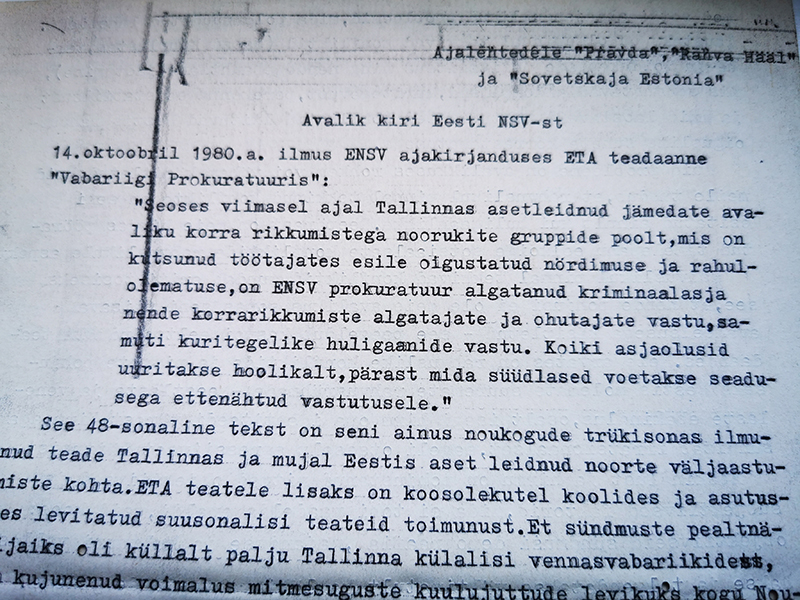

On 28 October 1980, 40 Estonian intellectuals signed a letter calling for the preservation of the Estonian language and culture and an end to Russification. The “Letter of 40” was addressed to the editors of the Soviet newspapers Pravda (The Truth), Rahva Hääl (The People’s Voice), and Sovetskaya Estonia (Soviet Estonia). The KGB tried to influence the signatories (through “prophylactic policing”) to withdraw their signatures, but the majority did not. One of the signatories, Marju Lauristin (b. 1940), minister of social affairs of the restored Republic of Estonia (1992–1994) and a professor at the University of Tartu, later said, “The Letter of 40 was also significant because it was the first time in the Soviet system and circumstances where Estonians could express themselves en masse. It can even be compared to the social media effect, as the letter spread among friends and acquaintances, and it became impossible to keep a tally of how many copies were distributed across Estonia.”

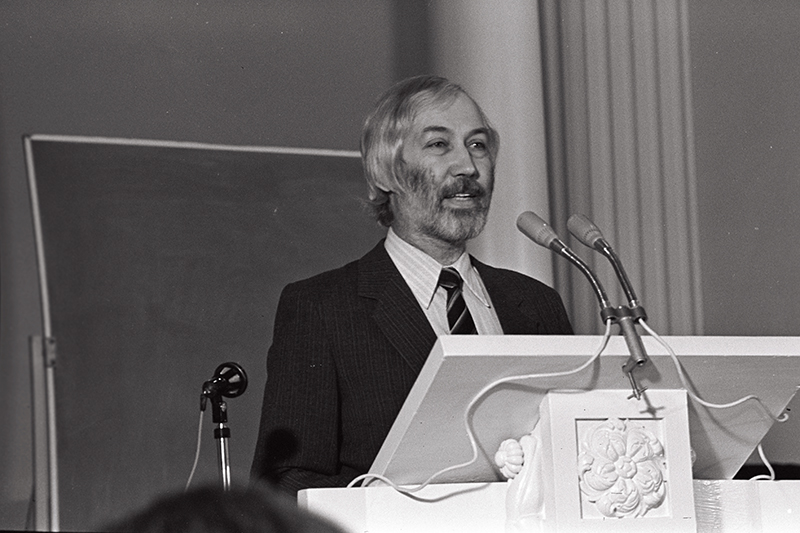

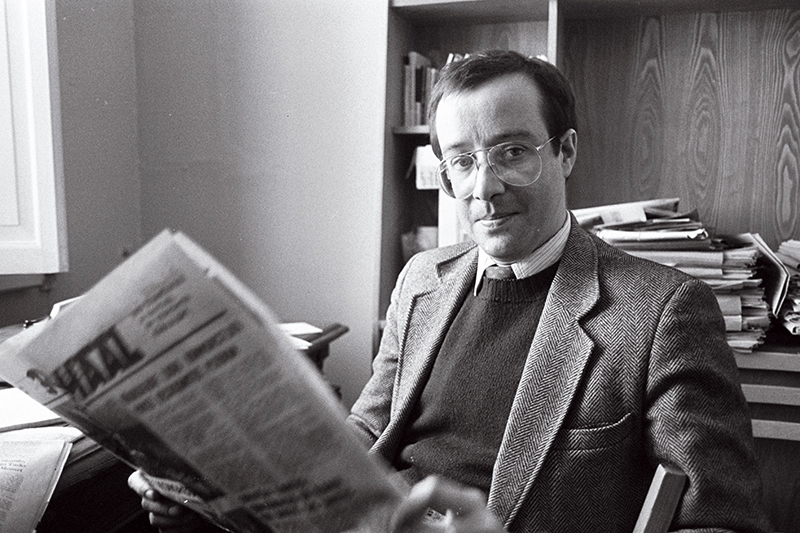

One of the signatories of the Letter of 40, Andres Tarand, later Prime Minister of the restored Republic of Estonia 1994–1995. He was also the one who posted the letter at 8.15 am on 4 November 1980. In 1980, Andres Tarand was the research director of the Tallinn Botanic Garden, and the letter was typed in his office. The Botanic Garden was located on a former farmstead of Estonian President (1938–1940) Konstantin Päts; Tarand’s office was in the farm’s kitchen. President Päts was arrested in 1940 and he died (1952) in a mental hospital in Russia. Forcing people into mental hospitals was one of the Soviet Union’s repressive methods against their political enemies.

Interesting facts

Toomas Kiho (b. 1963), editor-in-chief of the journal Akadeemia, then a high school student, recalls: “I received a copy of the famous letter from my classmate Toomas Tõldsepp – top secret, of course. I retyped several copies of it at home with trembling hands, directly through carbon paper. Afterwards, I anxiously and carefully discarded the used carbon paper sheets in the large communal rubbish bin in front of the house, to erase any traces of my anti-Soviet act. I sighed with relief when I soon saw the garbage truck take the container away…”.

General non-compliance after Stalin’s death

In addition to active and passive forms of resistance, there were also other forms of disobedience that cannot be strictly referred to as resistance. Alongside the economic decline of the USSR, general negative or indifferent attitudes towards foreign rule also undermined the Soviet regime’s authority. They included “adherence to bourgeois atavisms” such as observing church customs, making fun of occupation authorities in jokes, and getting past censors in the press and creative works (that is, transmitting hidden messages in a seemingly Soviet-friendly text). “Fawning over degenerate Western culture” included “material culture” procured from outside the USSR. This included “signs of Western culture” such as wearing jeans, long hair on men, the hippie movement, and later, the punk movement. Finnish TV could be received in Tallinn and Northern Estonia due to the short distance from Helsinki, Finland – fifty miles over the sea; for this, homemade antennae were installed on windows and rooftops, alongside special receivers called “Finnish blocks” on TV sets, as the signal transmission system of the USSR differed from the one used in Finland. The party condemned watching Finnish TV but, over time, turned a blind eye to the practice.

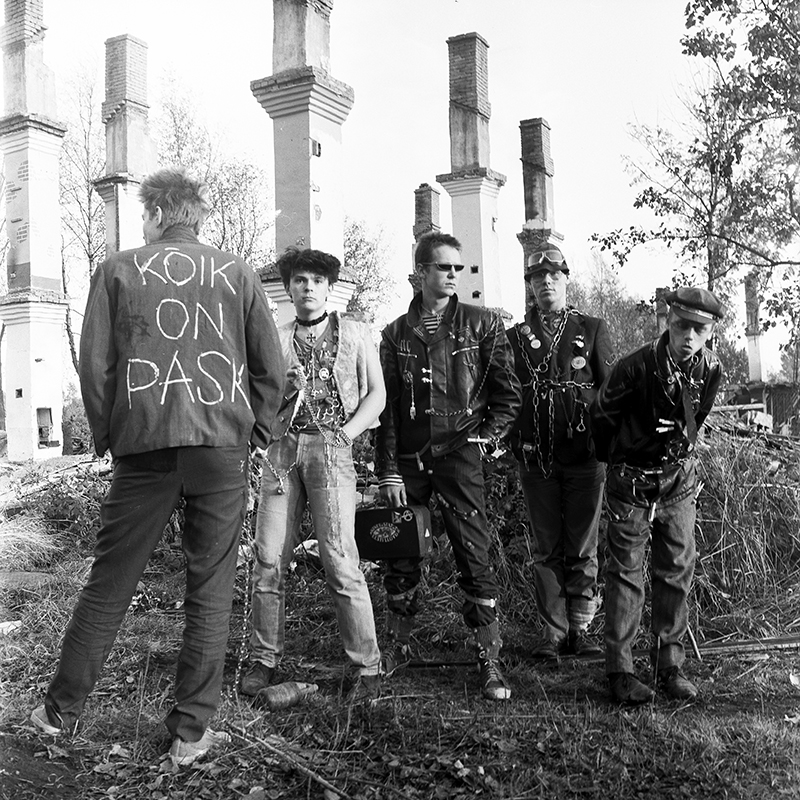

The punk subculture defies social norms, authority, and mainstream culture, which is why the Soviet order was the main target of criticism for Estonian punk. The young rebelled by wearing provocative clothing, engaging in shocking behaviour, playing in punk bands, acting up during concerts, as well as writing poetry and scribbling messages in public places. Pictured are well-known members of the Estonian punk subculture in 1982, including Villu Tamme, Urmas Tunderberg, Ivo Uukkivi aka Monk, Peeter Sepping and Anti Nõmmsalu alias Anti Pathique. Villu Tamme’s jacket reads: „Everything is crap“.

Historian Indrek Paavle (1970–2015) with his family in 1988, at his graduation from Tallinn Secondary School No. 36. Indrek is holding the national flag of Estonia – the entire class had unanimously agreed to bring it to the graduation ceremony. The principal was startled to see the flag, although national colours had already been brought out that spring as part of a public initiative. However, the deed was done. Indrek’s great-grandfather had bought this flag in the late 1930s; it had been brought along to several patriotic events. The family hid the flag from Soviet authorities in a chest of drawers; it now has a place of honour at the Paavles’ home.

One form of passive resistance was the preservation of symbolic items connected to the independent Republic of Estonia. If one was caught in possession of such items, it resulted in harassment by the authorities or more serious consequences. In 2004, an Estonian national flag was found hidden inside the organ of St. Olaf’s Church. The flag was wrapped in issues of the newspapers Sovetskaya Estonia (14 April 1946) and Rahva Hääl (11 August 1962).

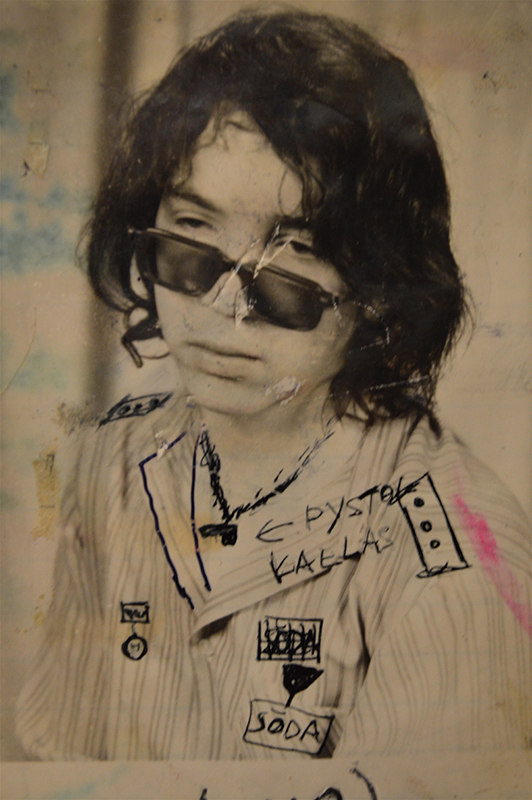

Journalist Juku-Kalle Raid (b. 1974) in 1989, at the age of 14. As military studies were included in the school curriculum and militarism was still emphasised, young people revelled in ridiculing it alongside other aspects of Soviet culture. Such mockery included depicting oneself as a Hero of the Soviet Union, as well as wearing defaced Soviet medals. Juku-Kalle wears a drawn medal that says “war”, with an additional note that says “pistol around the neck”. Young men wore their hair long as an expression of passive resistance, because such an appearance was considered inappropriate for “Soviet youth” and condemned in schools.

Interesting facts

In 1978, Linnar Priimägi (b. 1954) and Ants Juske (1956–2016) wrote an essay titled “The Tartu Autumn.” It was distributed, hand to hand, as samizdat (underground literature), read aloud on the Estonian-language programme on Radio Free Europe, and published in 1982 in Mana, a magazine for Estonian refugees abroad. The essay describes the relations and self-expression of the post-war generations: “Administratively, we do everything that is required, as much as necessary to stay afloat, and as little as possible to be free. […] Other young people are emerging alongside us. We have no money, they do. […] Contrary to our ideal, theirs is obvious. The youth of the 1960s wore a mentality, we wear indifference, they wear jeans. The youth of the 1960s attended discussions, we are simply hanging around, they go to flea markets and discos.” Both authors got in trouble with the authorities; Juske was forced to leave the postgraduate course at the University of Tartu “voluntarily.”

The ERSP and the MRP-AEG

On 20 August 1988, the Estonian National Independence Party (ERSP), the first non-communist political association in the Estonian SSR, was founded. The forerunner of the ERSP was the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact Disclosure Estonian Group (MRP-AEG), which organised a demonstration in Tallinn’s Hirvepark (Deer Park) on 23 August 1987 calling for the disclosure of the secret protocol to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (which put the Baltics in the Soviet sphere of influence). At the founding of the ERSP in Pilistvere, former political prisoners Mati Kiirend, Lagle Parek, Erik Udam, Eve Pärnaste, and Vello Salum were elected to the party’s board of directors. The party’s aim was to restore the independence of occupied and annexed Estonia. After the Republic of Estonia regained independence in 1992, the ERSP won 10 seats and joined the government coalition.

Interesting facts

ERSP member Kristina Märtin (b. 1973) was deputy secretary at the ERSP office when the constitution was drafted: “My role was to empty the ashtrays, make coffee or tea, and cut the cake. On one occasion I put the tea bag on the edge of the saucer, poured the cup full of hot water, and took it to Vardo Rumessen (1942–2015), a member of the Constitutional Assembly. Vardo was so engrossed in his work that he didn’t look at the cup and just reached out and started drinking. I froze in horror, but I didn’t dare say anything. There was no need – Vardo happily drank the boiled water. The constitution really was hard work!”

The Singing Revolution

Spontaneous night-time song festivals began during the Tallinn Old Town Days event in 1987. They became popular events for young people, symbolically uniting them during the period of national mass demonstrations in Estonia from 1988 to 1991.

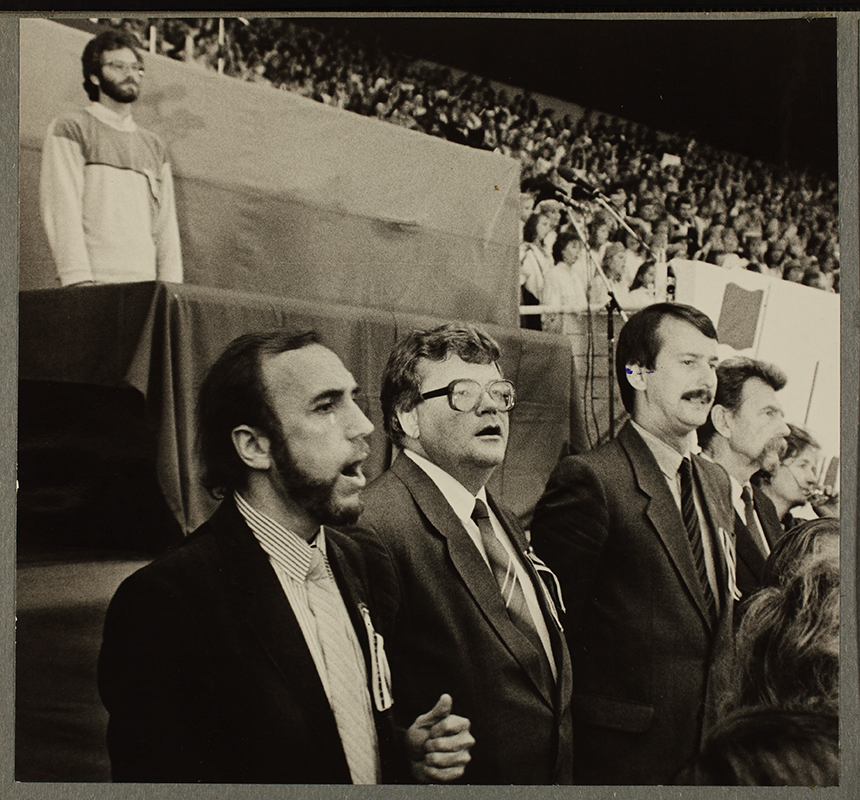

In 1988, the Popular Front of Estonia was founded. This organisation called for the democratisation of society, extensive autonomy within the USSR, and, starting in 1989, national independence. On 11 September 1988, about 300 000 people gathered for the “Estonian Song” concert organised by the Popular Front. In August 1989, on the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Popular Front, together with the Baltic Council and the Latvian and Lithuanian organisations Tautas Fronte (Popular Front of Latvia) and Sąjūdis (Reform Movement of Lithuania), organised the Baltic Way. This was a continuous human chain that stretched 400 miles across the Baltics, from Tallinn, Estonia to Vilnius, Lithuania. Nearly two million people thus demonstrated their desire for freedom. The international attention given to the Baltic Way played a major role in the process leading to the annulment of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocol at the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies in December 1989. In 2009, UNESCO recognised the Baltic Way as a phenomenon of non-violent resistance and documents concerning the Baltic Way were entered in the UNESCO World Memory Register.

The beginning of the Baltic Way at the foot of the Pikk Hermann (the Tall Hermann) tower in Tallinn, Estonia. Members of the Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Language and Literature, and the Institute of History stood at the beginning of the chain. The flag is held by linguist Madis Norvik. The Tall Hermann tower is situated next to the Estonian Parliament building, the flag on the top of the tower being one of the symbols of the government in power.

Interesting facts

Mart Tarmak (b. 1955) was one of the initiators of the idea for the Baltic Way. The inspiration for forming a human chain came from a working bee in the summer of 1988. At the invitation of the Popular Front, thousands of volunteers dug an electrical cable ditch for the National Library of Estonia in one day, something builders and subcontractors had not managed to do for months. Concerning the human chain, initial proposals called for it to stretch from Tallinn east to Narva. At the same time, the idea for a collective public protest took root in Lithuania. One early idea was to use a human chain to form the letters M, R, and P, and for each Baltic state to form one of the letters.

Declaration of Independence on 20 August 1991

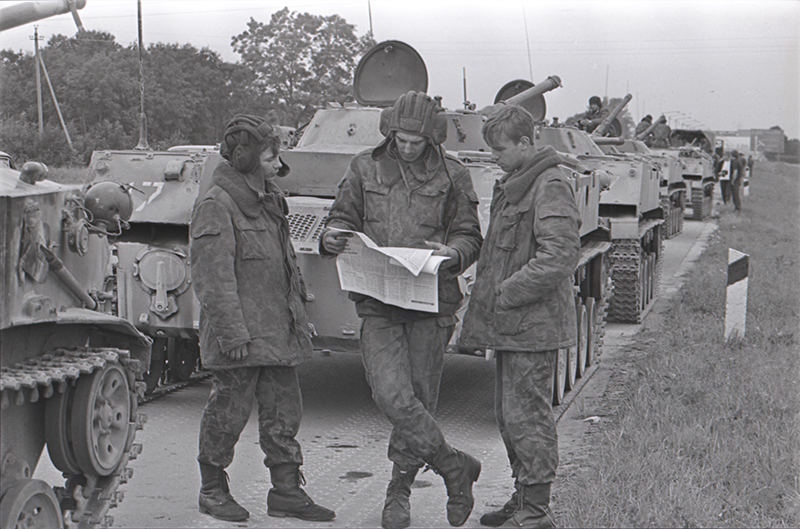

In March 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), the name the Soviet occupying regime gave to Estonia, declared that the authority of the Soviet Union in Estonia had been illegal since its establishment, and announced the restoration of the Republic of Estonia. In May, the Estonian SSR was renamed the Republic of Estonia. However, the leadership of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) continued to regard Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as Soviet republics subordinate to Moscow. In January 1990, Soviet special forces tried to occupy media and communications centres controlled by national forces in Vilnius, Lithuania and Riga, Latvia, killing about a dozen people. Estonia was fortunate to escape such bloodshed. On 13 January, Boris Yeltsin, chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, arrived in Tallinn, where he and the leaders of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania signed a joint statement recognising each other’s national sovereignty. Pro-imperialist communists made one last forceful attempt to restore the Communist Party’s monopoly on power and suppress the independence aspirations of the republics. On 18 August 1991, they ousted Mikhail Gorbachev (General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) and declared a state of emergency. Two days later, on 20 August, the Estonian Supreme Council adopted a resolution on the independence of Estonia, thus restoring the Republic of Estonia, which had been founded in 1918 and occupied by the USSR in 1940. By 21 August, the coup had failed; what followed was the final breakup of the USSR in December 1991.

Interesting facts

Entrepreneur Tiit Pruuli (b. 1965): “In August 1991, I worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as press secretary to Lennart Meri. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was located in the right wing of Toompea Castle that houses the Parliament of Estonia.

“On the first morning of the coup, I drove to work from [the residential district of] Lasnamäe in my mother’s new red Lada (Soviet car brand). I parked the car in front of the castle. An hour later, the castle commandant found me and said: ‘Get your beautiful car out of here, or there may not be much left of it.’ Large blocks of stone were taken to Toompea as barricades. And men armed with machine guns appeared in our corridors.

“During lunch, I took one of the two ministry mobile phones to Lasnamäe. We sent messages to our friends around the world saying that if other channels no longer worked, they could use this number to keep in touch. That apartment on Läänemere Street might have become the last office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”

Resistance in exile - Foreign missions

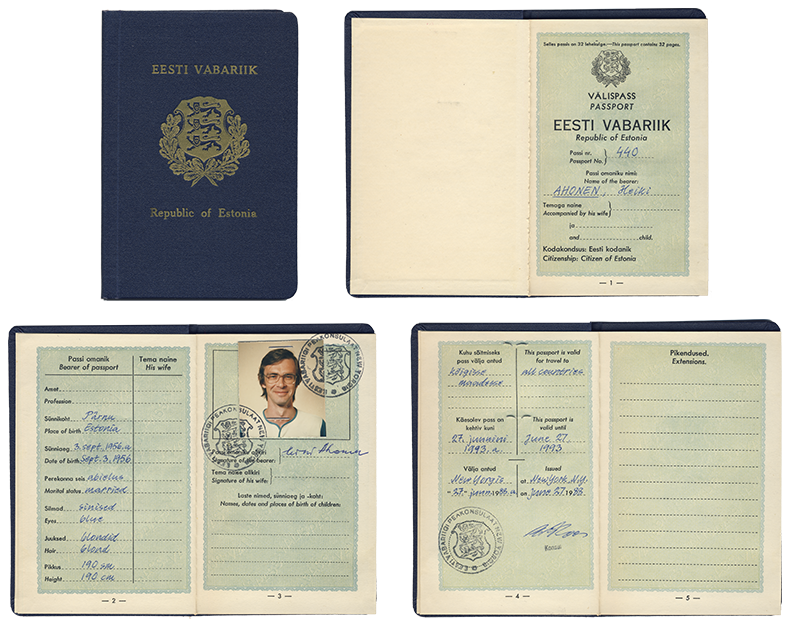

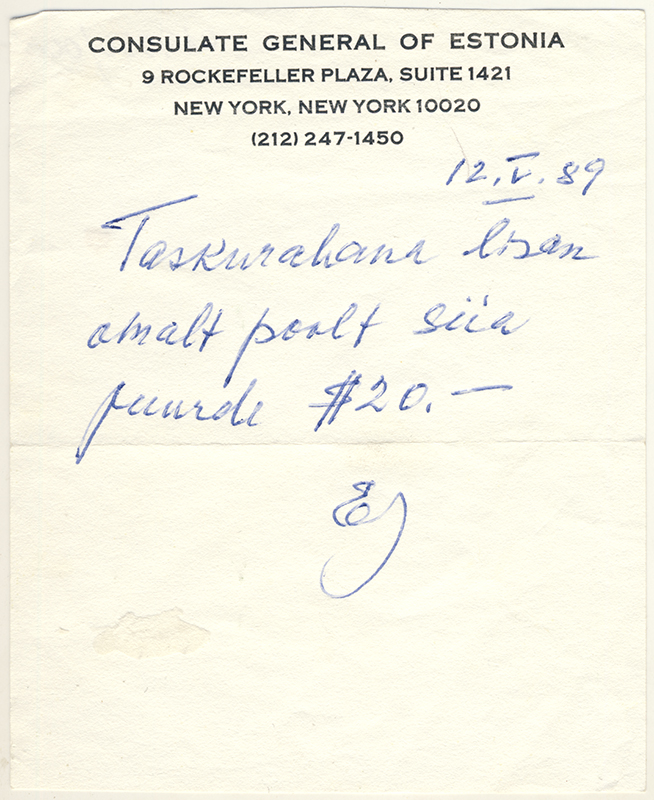

When the Soviet Union occupied the Republic of Estonia, Estonian diplomats decided to continue their work abroad, even though the Soviet Union threatened to shoot all Estonian diplomats who refused to return to their homeland within 24 hours. The diplomats’ work helped ensure that Western countries did not recognise the occupation and annexation of the Baltic states. The policy of non-recognition lasted from 1940 to 1991. The United States, the Vatican, and Ireland maintained this most consistently and never gave de jure or de facto recognition to the Soviet occupation of Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania. Out of all the Estonian foreign missions, the consulate general in New York, with consul general Ernst Jaakson (1905–1998) acting as ambassador, managed to last throughout the entire occupation period (1940–1991). Jaakson came to symbolise the legal continuity of the Republic of Estonia. The Estonian mission in New York was a small piece of free Estonia, flying the blue, black, and white Estonian flag, applying pre-occupation laws, and issuing some 20 000 Estonian passports – “Jaakson passports” – which were recognised as travel documents by many countries.

Interesting facts

On the wall of the lobby of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Estonia in Tallinn, there is a memorial plaque with 231 names. These are employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Estonia who, during the Soviet (1940–1941, 1944–1991) or German (1941–1944) occupations, were executed, arrested, deported, committed suicide to avoid persecution, or were forced to remain in exile in order to survive.

Resistance in exile - Demonstrations and legal briefs

Estonians who fled the occupation of their homeland played a major role in maintaining Estonian identity and communicating to the world what was happening in occupied Estonia. The largest Estonian communities were in Sweden, the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia. In addition to maintaining the government-in-exile and foreign missions and distributing materials received from dissidents, Estonians in exile wrote public letters to foreign governments and human rights organisations – above all, United Nations (UN) organisations – and organised demonstrations calling for Estonia’s independence. The most important gatherings for exiled Estonians were the ESTO – Estonian Cultural Days, organised every four years. First held in 1972 in Toronto, ESTO included many cultural events and gatherings of Estonian organisations from around the world. These had the political role of communicating to the world about occupied Estonia, but above all, they were an opportunity for interaction among the participants themselves. The tradition of ESTO continued even after the restoration of Estonia’s independence. The latest ESTO took place in June and July in 2019 in Helsinki, Finland, and in Tallinn and Tartu, Estonia.

Board of the Estonian Centre for the Assistance of Imprisoned Freedom Fighters, 1988. The organisation was founded in Stockholm in 1978 under the leadership of Ants Kippar (first row, second from left). Initially, its activities consisted primarily of helping the families of imprisoned dissidents. They compiled lists of dissidents detained in camps and psychiatric hospitals, and informed Western organisations about the situation in Estonia.

Interesting facts

Writer and medical scientist Enn Nõu (b. 1933), who escaped with his parents to Sweden in 1944, recalls: “With Helga [his wife, writer Helga Nõu, b. 1934] we took part in an event organised by the June Committee on 14 June 1964 at the Uppsala Civic Centre, where Birger Nerman, Bo Setterlind, and others spoke. It was organised by Arvo Horm. Wearing white student hats, we marched there in procession. Local communists waited at the door handing out counter-leaflets. The June Committee was organised to protest Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to Sweden. A live piglet, symbolising Khrushchev, was released in protest near the royal castle in Stockholm and eventually captured by the Swedish police”.

Resistance in exile - Radio stations

In the Soviet Union, the spread of uncensored information to and from the country was prevented by any means. Foreign radio stations, especially Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberty, were particularly problematic for the occupation authorities. Voice of America, operating since 1942, is an international broadcaster funded by the US government. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty were created at the outbreak of the Cold War and were funded by the US Congress. Radio Free Europe targeted the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, while Radio Liberty focused on the Soviet Union. Both stations shared information from the Free World to countries that did not have freedom of speech. Voice of America regularly broadcast in Estonian since 1951. The other two radio stations started broadcasting in Estonian after their merger in 1975. People listened to Western radio stations in spite of jammers and bans, because they were virtually the only source of uncensored news.

Interesting facts

In 1953, the USSR spent US $70 million to develop the technology to jam Western radio stations and US $17 million to operate the technology. By contrast, the total US budget for anti-Soviet radio stations was only US $22 million. There were an estimated 2 500–3 000 jamming stations in the Soviet Union and Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe. People listened to the stations despite the whistling and crackling noises caused by the jammers, because they couldn’t get uncensored information elsewhere.

On 23 August 1987, a demonstration was held in Hirvepark (Deer Park) in Tallinn, Estonia, condemning the crimes of Stalinism and fascism. Local authorities permitted the rally but did not allow information about it to be broadcast. Paradoxically, the invitation to gather for the demonstration spread via foreign radio stations and brought together thousands of people.

Estonians and resistance to Soviet rule in Canada*

* This special panel on the resistance to Soviet rule in Canada was produced in cooperation with the Estonian community in Canada in connection with the opening of the exhibition in Toronto.

During World War II, an estimated 80 000 people fled Estonia in the face of Soviet terror. Most of them were civilians.

The mass exodus occurred after the reinstitution of Soviet occupation in 1944. Although they fled with the hopes of returning home soon, most of the refugees never saw their motherland again. Many never even saw the freedom they sought in exile because, in addition to the toll taken by the autumn storms of the Baltic Sea, Soviet submarines also claimed their fair share of blood. It is estimated that 6–9% of refugees died on the journey.

Approximately 14 000 Estonian World War II refugees arrived in Canada. In most cases, they did not speak the local languages, which did not leave them with many options for earning a living and obtaining an immigration permit. However, the relatively high level of education of the refugees allowed them to gradually improve their living standards and better adapt to conditions in Canada, while still maintaining their Estonian identity. In order to preserve their language, culture and traditions, as well as join the struggle for restoring the nation’s independence, they assembled into local Estonian societies. In 1949, when there were already fifteen of these societies, the central organisation uniting them, the Estonian Federation in Canada (Eestlaste Liit Kanadas), was established. The Estonian Central Council in Canada (Eestlaste Kesknõukogu Kanadas), an organisation within that association, was formed in 1951 with the specific aim of drawing international attention to the Soviet occupation of Estonia as well as the crimes against humanity and human rights violations committed by the occupation regime. The purpose of the council was to ensure the unity of dispersed Estonians in the efforts of restoring the Republic of Estonia, and now, of maintaining it. This was aided by the supportive stance of the Canadian government, who, despite being pressured by the Soviet Union, never recognised the occupation rule in the Baltic states. Public acknowledgement of the legitimacy of the Republic of Estonia was given in 1984 when the Prime Minister of Canada, Brian Mulroney, made an appearance at the Global Estonian Cultural Days (ECD). On 26 August 1991, his government also became the first of the world powers to recognise the restoration of Estonia’s independence.

In 2000, there were approximately 28 000 Estonians living in Canada, most of whom were war refugees and their descendants. They all have their role in restoring and maintaining free Estonianness in both Canada and back home in Estonia.

Estonian House in Toronto. The consulate opened its doors here in 1951 and operates in the building to this day.

In 1951, the Consulate of the Republic of Estonia opened its doors in Toronto, and with consent from the Government of Canada, the Estonian Consul General in the United States, Johannes Kaiv, appointed Hans Johannes Ernst Markus (1884–1969) as the first consul. Opening a consulate during an occupation of the state by a dictatorship is an act of political protest and a gesture whose significance is difficult to overstate. For a long time, the consular office of Markus was not fully recognised, although he had the power to issue passports of the Republic of Estonia. Starting from 17 August 1962, however, Markus was officially recognised as the Estonian consul and he was also included in the issue of Canadian Representatives Abroad and Representatives of Other Countries in Canada. The consul and consulate provided the Canadian government with objective information about the situation in Estonia, the human rights violations committed by the Soviet occupation regime and the efforts of Estonians to regain their freedom.

In 1952, the first Estonian Freedom Fighters Association (Eesti Võitlejate Ühing) in Canada was founded in Montreal, which together with similar organisations in other Canadian cities formed the World Legion of Estonian Liberation in Canada (Eesti Vabadusvõitlejate Liit Kanadas). The latter was joined by the Estonian Veterans of Finnish War (Soomepoiste Klubi), the Airforce Recruits Association (Lennuväepoiste Klubi) and the Association of Estonian Officers (Eesti Ohvitseride Kogu Kanadas). Besides organising shooting exercises and competitions, the legion also took part in anti-Soviet demonstrations, drafting protest letters, publishing booklets, etc. Every year a ceremonial meeting was held to mark the beginning of the War of Independence. In 1975, there were more than five hundred former Estonian soldiers organised in Canada. After the restoration of Estonia’s independence, the association reorganised its activities to offer moral and economic support to the Estonian Defence League (Kaitseliit), the importance of which is difficult to overestimate given the sparse conditions of the time.

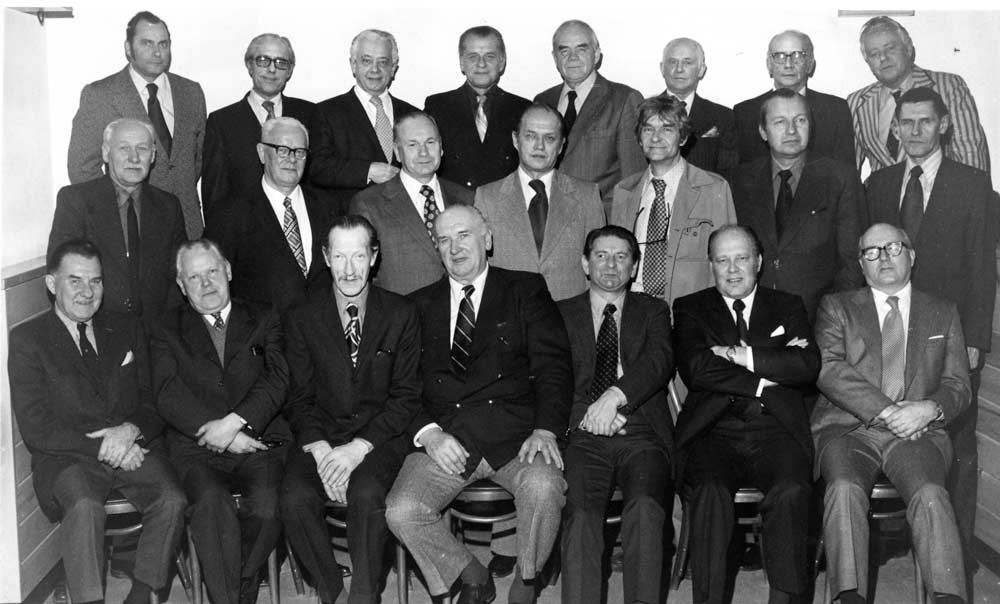

Estonian Freedom Fighters Association in Canada 1974.

In the first row (from left): B. Rahe, L. Mesina, A. Remmelkoor, R. Viksten, K. Steinberg, G. Juuse, G. Soans.

In the second row (from left): H, Riga, H. Meret, E. Mägi, L. Pikkov, J. Prii, G. Tirman, H. Kivi.

In the third row (from left): F. Tamm, G. Mitt, R. Edari, L. Vesk, O. Lainurm, B. Randalov, A. Jaagumagi, H. Kesker.

IX Baltic Evening on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, 1981.

In 1949, the Baltic Federation was founded in Canada to promote cooperation between Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Together with the Estonian Central Council in Canada, the federation organised several memoranda and demonstrations against the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States, and starting from 1973, a series of political discussions known as Baltic Evenings were held at the Canadian Parliament in Ottawa. Every Baltic Evening was attended by members of the Canadian Parliament, ministers and sometimes the incumbent prime minister. These gatherings contributed to the early recognition of the restoration of the independence of the Republic of Estonia by the Canadian authorities on 26 August 1991, six days after its proclamation in Tallinn.

Interesting facts

Estonian-Canadian Siiri (Oder) Aulik (b. 1967) returned to her roots in Estonia when the Estonians were still struggling to restore their independence. She recalls: “During the Soviet coup d’état attempt, we were all working day and night at the foreign ministry in Toompea, the site of both the parliament and government. Giant boulders blocked the roads, and the windows on the upper floors had been barred in case paratroopers landed on the roof. Soviet tanks had rolled into Tallinn, so there were Kalashnikov-armed guards in the hallways. On the night of 20 August, they asked me not to leave, as parliament was about to adopt a bold resolution confirming the de facto independence of Estonia, and it had to be translated into English to be faxed out to the world as soon as possible. I was both thrilled and terrified at what this might mean. Knowing what a huge responsibility it was to get the legal and diplomatic language just right, I called my Estonian-Australian friend Tiia Raudma to come help me, and together with our local colleagues we carefully weighed each word and phrase of The Republic of Estonia Supreme Council Resolution on the National Independence of Estonia.”

THE EXHIBITION HAS BEEN COMPILED BY:

Estonian Institute of Historical Memory, 2021

Curator: Eli Pilve

Compiled by: Eli Pilve, Peeter Kaasik, Toomas Hiio, Martin Andreller

Edited by: Toomas Hiio, Laas Leivat

Translation: Refiner Translations OÜ, Elmar Gams, Marju Meschin, Luisa Tõlkebüroo OÜ, Maria Rist

Proofreading: Elmar Gams, Marju Meschin, Maria Rist, Ross Seymour

Designer: Anni Vakkum

Photos:

Estonian History Museum

Estonian National Museum

Estonian Museum Canada

Tartu Art Museum

Tartu City Museum

Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom

National Archives of Estonia

Association of Estonians in Sweden

Toomas Kiho

Mart Meri

Enn Nõu

Silja Paavle

Verner Puhm

Juku-Kalle Raid

Arno Saar